By David Marcus

Tuesday, June 04, 2019

Incubation Under Obama

Barack Obama was a problem for the New Progressive

movement. At Occupy Wall Street, many of his policies were attacked, but still

with a kind of deference due to him being the first black president. And while

Obama may have always been more leftist than he let on — for example, his

abrupt “evolution” on gay marriage — he presented himself as a moderate.

Progressives, especially white progressives, had to be

careful in attacking him. Some notable black progressives such as Tavis Smiley

and Cornel West felt more comfortable taking aim, but in general the New

Progressive movement had to bide its time.

During the four years from 2012-2016, the movement made

spectacular cultural inroads with everything from movies to news to advertising

to corporate culture. By the end of this period, terms like intersectionality

and privilege theory had become household words.

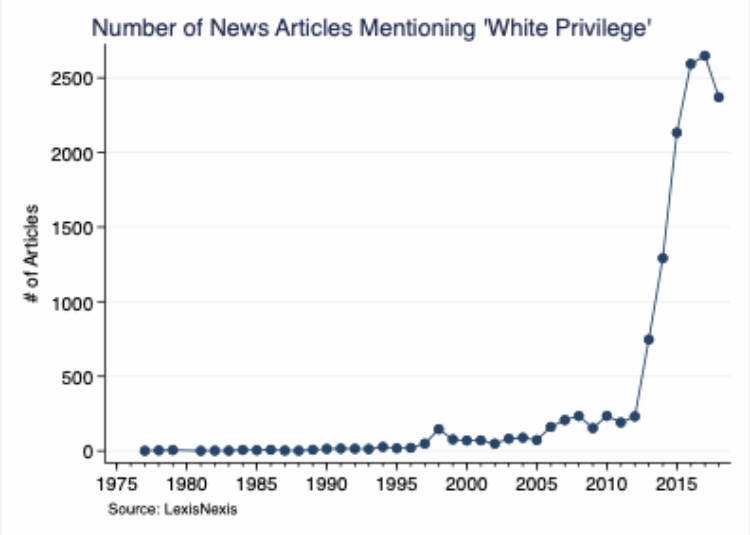

In a recent and remarkable Twitter thread,

Zack Goldberg shows graphs of searches on LexisNexis for far-left terms like privilege,

intersectionality, and a host of others. They go from barely a blip to

soaring heights in this period. The beginning of the upswing in almost every

case is about 2010, but it wasn’t until 2012, just as the embers of Occupy were

dying out, that the vast increases occur.

By the end of 2012-2016, a socialist very nearly became

the Democratic Party’s nominee for president, and the New Progressives were

poised to capture real political power.

Changing Racial Attitudes

In February 2012, not long after the barricades came down

in Zuccotti Park, Trayvon Martin, a black 17-year-old in Florida, was

tragically gunned down by George Zimmerman. Martin’s crime? Looking suspicious

to Zimmerman.

It was the first of many media-highlighted incidents that

cost young black men their lives. Some were even caught on video owing to the

promulgation of camera phones. These events, along with a spate of police

shootings, spurred the creation of the Black Lives Matter movement and marked a

sharp and devastating decline in how Americans felt about race relations.

According to Gallup, at the start of 2013, 72 percent of

white Americans and 66 percent of black Americans said relations between whites

and blacks were “very good” or “somewhat good.” These were the highest combined

numbers ever recorded. By 2015, these numbers went down to 51 percent of whites

and 45 percent of blacks, in the sharpest dips in the polling that goes back to

2001.

While these racial attitudes were changing, a growing

movement in education, corporations, and social media was bringing

intersectional ideas based on privilege theory to the fore and beginning to get

some backlash. Where once Americans had a tacit agreement that treating

everyone equally was the key to better race relations, the New Progressives

rejected this notion, insisting that systemic racism made individuals’ good

intentions or actions more or less irrelevant.

Harkening back to the Occupy General Assembly’s

progressive stack, what emerged was an attempt to redistribute speech. In

practice, this gave the New Progressives license to de-platform, or silence,

speakers who would not show deference to the new identity rules. Calls to fire

professors, shut down speaking events, and boycott insufficiently leftist

companies started to define the New Progressives and further separate them from

traditional American liberalism.

The Expansion of Identity Politics

In May 2014, Kevin Williamson penned an op-ed in the

Chicago Tribune titled, “Laverne Cox is Not a Woman.” Cox was the star of the

TV show “Orange Is The New Black,” and at the time was the most famous

transgender person in America.

Cox embraced a new concept of transgenderism. This

concept, which Williamson and others (myself included) reject, holds that a

trans person does not merely live as, and appear to be a member of, the

opposite sex, but in fact is a member of that sex solely on the basis of

believing or “knowing” that they are. Williamson rejected this idea in his

article. For his trouble, he was shouted down as a bigot, and the Tribune

pulled his piece from their pages and website.

This was a major victory for the New Progressives. In the

blink of an eye, sex, one of the most foundational elements of humanity, had

been turned on its head. This was not a change anyone voted for. There was no

meaningful public discussion about it. In fact, as seen above, it wasn’t

allowed by a major outlet, instead it was simply decided upon by cultural

elites who called any pushback against their radical ideas bigotry.

To justify this illiberal policing of speech, the New

Progressives argued that any speech that “misgenedered” a trans person was

tantamount to violence against vulnerable trans people. Using this prototype,

over the next several years, all kinds of speech was condemned as violence and

therefore deemed appropriate for censorship.

Soak the Rich

While the identity politics of the New Progressives was

taking over in our nation’s cultural spaces, the socialist fixation on income

inequality was gaining important adherents in our politics. Two primary figures

emerged to beat this drum, both U.S. senators. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and

Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts used the concept of income inequality to

marshal support in the Democratic Party in favor of socialism and away from the

neoliberalism of Bill Clinton, and even Barack Obama.

On this fight, the New Progressives found some unlikely

allies on the right. Since at least 1992, when Ross Perot ran a centrist

anti-globalism campaign against Clinton and George H.W. Bush, both of whom were

more or less globalists, anti-globalism has been an outlier in both parties.

With the emergence of Sanders in the Democratic Party, this began to change.

The idea of drastically, rather than moderately,

increasing taxes on corporations and the richest Americans got a foothold in

mainstream Democratic politics. Perhaps more importantly, the word socialist

began a rehabilitation tour in the United States. Even though the financial

crisis was over by 2012 and living standards were increasing, Warren and

Sanders still insisted that American wages needed to be more equal. For many on

the left, this became quite persuasive.

From Big Corporation to Small Christian Business

Although the Citizens United decision and a

conservative Supreme Court to protect it assured that the New Progressives

could not block corporations from engaging in political speech, they soon found

a new kind of business to target with illiberal attempts to limit First

Amendment protections. In this case, Christian small business owners who

refused to accept creative jobs that expressed acceptance of gay marriage were

attacked.

The crux of these cases had nothing to with actually

serving gay customers, but a baker or photographer using her creative skills to

create a positive statement about people of the same sex getting married. These

Christian shopkeepers argued that if the state forced their participation in

gay marriage, it was compelling them to make statements against their religious

principles.

The shopkeepers were backed up by the 1994 Religious

Freedom Restoration Act sponsored by Chuck Schumer, then a House

representative, and signed into law by Clinton. This law said if the government

had a reasonable interest in limiting religious liberty, it must do so in the

least restrictive way possible. There were myriad ways for gay couples to get

the services they needed from businesses without religious objections;

therefore, what interest did the government have that allowed them to take the

drastic step of compelling speech?

The New Progressives had now launched a two-front war on

the First Amendment. In regard to large corporations, they sought to limit

speech. In the case of smaller, Christian-run corporate entities, they sought

to compel speech. Compelling speech was also taken up by the emerging trans

movement in demands that “preferred

pronouns” be used in public settings, even in some cases in Canada, Europe, and

New York City passing laws that punished using the wrong pronoun.

But even as universities and media style guides adopted

this new normal, new voices started to appear who refused to engage in

compelled speech. Bloggers, professors, and YouTube stars that questioned the

quick-paced changes in speech regulation began to form a constellation of

resistance to the New Progressives. Only later did this resistance come to be known

as the Intellectual Dark Web.

Enter Bernie

The most significant event during this period of

incubation for the post-Occupy, New Progressive moment was Sanders’s candidacy

for the Democratic presidential nomination. Of the three main Occupy platform

planks — identity politics, income inequality, and anti-corporatism — Sanders

checked the latter two boxes in ways no candidate ever had before.

For the presumptive and eventual nominee, Hillary

Clinton, this socialist challenge was uncharted territory. Never before had a

mainstream Democrat had to seriously engage such far-left ideas, and it left

her positions in a fragile state. Nowhere was this clearer than in regard to

the Obama administration’s proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership. Clinton, who had

once called the deal the gold standard, suddenly came out against the TPP in

the fall of 2015 while campaigning against Sanders.

This shift flew somewhat under the radar because Donald

Trump, who at that point had become the presumptive Republican nominee, also

opposed the trade deal, although perhaps for somewhat different reasons. But

this was part of a larger trend of Hillary Clinton throwing mainstream

Democratic ideas, and to some extent her husband’s legacy as president, under

the bus. That plan did not work out very well for her.

While covering the 2016 Democratic National Convention in

Philadelphia, I saw the largest protests I had seen since Occupy. It is

important to understand the virulent anger these left-wing protesters felt

towards Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party. Trump wasn’t the only one

chanting “lock her up” in 2016. The overwhelming sense was that a new, young

progressive movement was rising either in opposition to the Democrats, or with

an eye to taking over their party and platform.

The Democratic Party establishment attempted a kind of

rhetorical appeasement. Phrases and ideas from the New Progressives were

adopted, but in slight ways. This was meant more to bring them into the fold,

maybe even to a seat at the table, but not to acquiesce to them. Had Hillary

Clinton become president, this plan might have worked, but indeed she did not.

On the night of November 8, 2016, Trump shocked the

world, and won the presidential election. It was a transformational moment in

American politics. It opened the door for the New Progressives to increase

their influence and venture into campaigning for political office. No longer

merely a cultural force to be contended with, they had become a viable

political faction in America.

The incubation period was over. The moderate forces in

the Democratic Party had lost, and they no longer had the power of Obama’s

charm and historical accomplishment to keep the new radically leftist movement

conceived at Occupy at bay. Everything changed that night, and the New

Progressives were poised and prepared to take advantage of it.

In Part 3, we will look at how the New Progressives used

Trump’s victory, and the vituperative anger so many Americans felt towards him

to establish a foothold in the highest levels of American power. Had their time

finally come? If so, would they push the Democrat Party so far left that its

center would not hold?

No comments:

Post a Comment